By Doug Chandler, FCIA, speaker at act22, the CIA’s annual conference

Introductory presentations on pension plans often begin with an explanation that there are two kinds of pension plans: defined contribution and defined benefit. The presenter goes on to explain that the individual plan member takes all the risk in a defined contribution pension plan whereas the employer takes all the risk in a defined benefit plan. The problem with this starting point is that none of it is true.

The thing we like to call a defined contribution pension plan is a savings plan that rarely leads to a monthly income in retirement – not a “pension plan” at all.

Defined benefit pension plans with fully insured benefits might have existed in Canada in the 20th century but it would be hard to find one today. One way or another, risk has at least partly shifted to plan members over time. There are still some employer-sponsored pension plans that are described as defined benefit but, if you dig a bit deeper, you will discover a variety of ways that favourable or unfavourable outcomes end up impacting benefits – contribution refunds, surplus ownership, benefit reductions when the sponsor is in financial distress or bankrupt, or conditional inflation protection. Unlike in the US and UK, very few 21st century Canadian defined benefit pensions are insured or fully guaranteed1.

The good news is that Canadian employers and unions have developed a range of risk-sharing pension deals suitable to their situation. If a Canadian worker is earning benefits in an employment-based pension plan today, it is likely either a jointly sponsored plan for public sector employees or a union-sponsored multi-employer plan. Recent innovations are paving the way for pension deals suitable for non-union and private sector employers too. Some of the new pension deals are variations on the theme of jointly sponsored plans or multi-employer plans, but one innovation in the tax rules – the Variable Payment Life Annuity (VPLA) represents an entirely new kind of pension plan. So, all told, there are four kinds of pension plans:

- Defined Benefit plans that have an employer-sponsor who bears most of the risk for as long as the plan (and the employer) survives, but that would rarely rise to the level of the pure defined benefit pension plan imagined in one of those introductory presentations.

- Contribution Partnerships, including public sector jointly sponsored pension plans, with contributions by participating employees and employers that fluctuate from time to time to absorb fluctuations in aggregate cost.

- Target Benefit plans, including union-sponsored multi-employer plans, with fixed contributions and a defined benefit formula but an adjustment mechanism that will allow pensions to increase or decrease from time to time to absorb fluctuations in aggregate cost

- Asset Share plans that will follow the pattern established by the new VPLA tax regulations and operate much like savings plans except account balances that would normally be left behind after a pensioner dies are used to support larger pensions for all plan participants

For the most part, we are ready for all of this innovation and diversity. Accounting standards, tax limits on contributions and benefits, methods for calculating Pension Adjustments (to integrate employer-sponsored retirement plans with personal Registered Retirement Savings Plan contribution limits) and actuarial guidance for lump sum settlement values have provisions suitable for these four types of pension plans. One challenge remains – provincial regulation of the adjustments required to benefits.

Provincial regulation seems stuck in the paradigm of two types of pension plans: if it’s not a savings plan, it must be a defined benefit pension plan with guaranteed benefits. And if the benefits are not guaranteed, the objective of regulation would seem to be to make benefit reductions as unlikely as possible. This can be a problem for plans that share risks among contributors. Rather than requiring the employer-sponsor to underwrite the risk of poor investment performance, the effect is to create inequities between generations of plan participants. Current contributors must build up reserves to protect the benefits of current pensioners and those reserves must be held for the benefit of future generations of contributors. While this sort of a deal might work in some situations, it fails to make pension plans at the defined contribution end of the spectrum competitive with a Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF) and other types of non-pension retirement income.

Most provincial and federal pension funding laws no longer apply solvency regulations to pension plans that are not backed by an employer-sponsor, but the perception that a pension should be more like an annuity than an RRIF remains. Regulations specify a minimum target level for pension fund assets, rather than addressing intergenerational equity or the way risk is communicated to plan members. Decisions about the balance between stable contributions and stable benefits are imposed by legislators, rather than being set in a way that reflects the circumstances of each enterprise and each employee group.

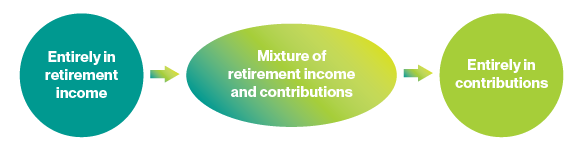

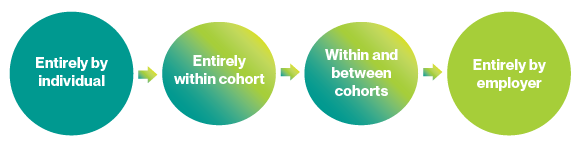

How are gains and losses absorbed?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to risk-sharing in employment-based retirement income arrangements. Some sponsors are keen to attract and retain career employees, while others simply want to offer a competitive compensation package for the duration of a project or gig. Some are concerned with fluctuations in cash flow, while others are focused on maintaining transparent and stable enterprise value from day to day and quarter to quarter. With the disappearance of traditional defined benefit pension plans in the private sector, the question legislators must ask is “will a new risk-sharing pension plan be better than a savings plan?” The maximum rate of drawdown should be compared to the limits on RRIF withdrawals, not the price of an annuity.

Doug Chandler, FCIA, has completed a number of research projects co-sponsored by the Canadian Institute of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries. His research paper, Classification of Risk Sharing Pension Plans – Canadian Practices and Possibilities, is available on the CIA website. He is an Associate Fellow at the National Institute on Ageing.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and does not represent an official statement of the CIA.

[1] Ontario operates a Pension Benefit Guarantee Fund that partially protects pensions for private sector single-employer pensions accrued in Ontario-regulated employment. The cost is borne entirely by the shrinking pool of employers who still offer this kind of pension plan.