By Chris Fievoli, FCIA, CIA Staff Actuary

The Rolling Stones are back on tour this fall, despite the recent passing of drummer Charlie Watts, proving that old age and impending mortality don’t have to be impediments when it comes to being a rock star. Frontman Mick Jagger is 78 years old, but you would never know it from this 2019 rehearsal video. And even though Keith Richards looks to be well into his hundreds, he is still going strong, and at this point will probably never die.

But they’re not the only ones. Several performers from the classic rock era – Elton John, Rod Stewart, Paul McCartney, and Eric Clapton, to name a few – can still be seen making new music and touring, even as they reach ages when most of us hope to be well into retirement. Admittedly, some of these performances are billed as “farewell tours,” but The Who demonstrated how much credence we can assign to that term.

And speaking of The Who, who famously declared, “I hope I die before I get old,” it’s obvious that they were wrong. Rock stars from the late 1960s and early 1970s have, in later life, shown themselves to have great staying power and impressive longevity – especially noteworthy in a field where too many talented performers died at tragically young ages. It’s as if there is some weird mortality inversion, whereby if a musician can survive the turbulent early years of their career, they can expect to enjoy a longer than normal lifespan. It almost sounds like something that could lend itself to an actuarial analysis.

What follows below is very much back of the envelope, and probably full of erroneous assumptions, but it’s a start. Assuming that 1970 is the apex of the classic rock area, I took a sample of 40 bands that were around that year, consisting of 186 members, and tracked the survivorship of their lineups for the subsequent five decades. The Stones and The Who are there, as are The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Pink Floyd, The Stooges, Genesis, and others. It’s a solid lineup – even more impressive than Woodstock.

For a mortality assumption, I was fortunate to stumble across period life tables produced by the US Social Security Administration, which actually go back to 1900 and project forward to 2095. These tables help address the thorny problem of how to reflect historical mortality improvement, and despite the fact that there are a fair number of Brits and Canadians in my sample, I deemed it to be good enough for now.

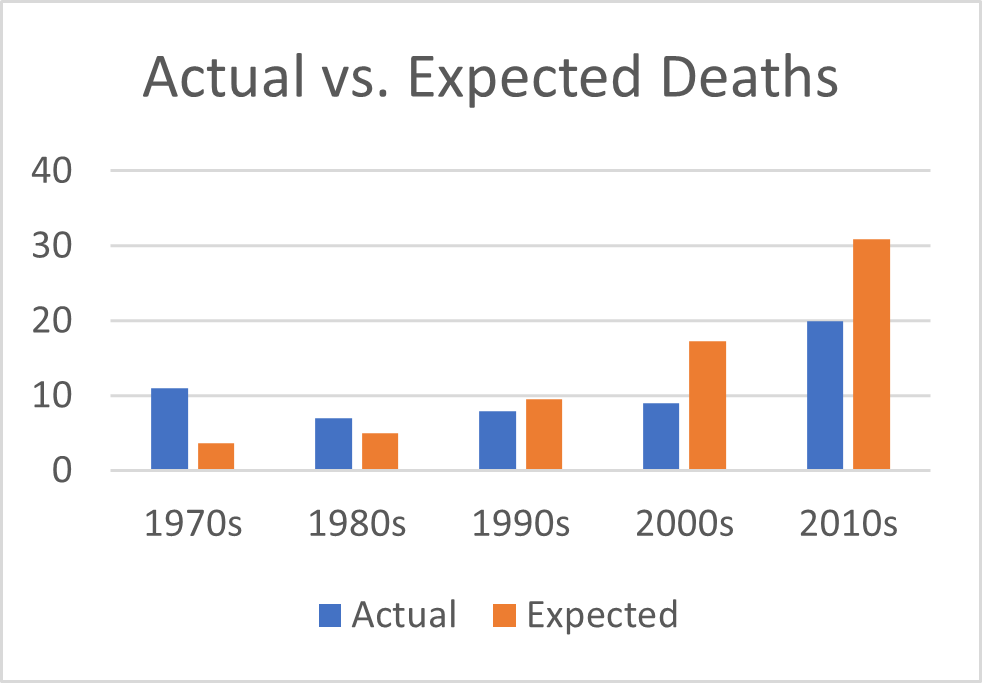

With this in hand, I took the cohort of musicians alive at the start of each decade, calculated the expected number of deaths for each subsequent ten year period, and compared this to the actuals. If my theory was correct, I would expect to see excess mortality in the 1970s and 1980s, but better than expected results as we get into the 2000s and 2010s.

Keeping in mind that this is a ridiculously small sample size, here’s what we get:

Is there something to this theory? I would say definitely maybe. Classic rock star mortality was horrible in the 1970s (thank you Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Duane Allman, and others), but seems to have evened out about thirty years ago, and has been quite good ever since.

As to why we see this, I will offer a few possible explanations:

- The natural selection effect: Let’s face it; if you have a strong enough constitution to make it past age forty as a rock musician, then you probably have a better overall genetic makeup than the average person.

- The “scared straight” effect: Maybe having seen some of their colleagues die young was incentive enough for today’s survivors to get their affairs together and start living a healthier lifestyle.

- The Napster/Spotify effect: Most classic rock performers likely expected to enjoy a long retirement funded by fat royalty cheques. But when CD sales cratered thanks to file sharing and eventually streaming services, it became necessary to get back on the road and into the studio to maintain an income. That by itself may have been sufficient incentive to get them to look after themselves.

Whatever the case may be, Father Time remains undefeated. Most of these artists will be entering their eighties in the coming decade, and we all know what mortality rates start to look like at that end of the table. So if you get a chance to see some of your favourite artists perform, take advantage of it, because no one gets to live forever.

Except maybe Keith, of course.

Special thanks to fellow Staff Actuary (and fellow music afficionado), Joseph Gabriel, FCIA, for his peer review.

The following comments were shared by readers:

Shannon Patershuk: Congratulations on a contemporary look at an age old mortality question. Music appeals to all age groups and is an excellent medium for communicating the drivers of longevity in the entertainment professions. It’s also an education or reminder of the influences in this genre. It makes for an enjoyable experience, especially with the video clips and clear writing style. Will the next study be on another exciting profession?

Chris Fievoli: Thanks Shannon – this happened to be an opportunistic intersection of personal and professional interests, where there was an actual theory I wanted to test out. I don’t know if something else will come along that checks all those boxes, but who knows?

Renee Couture: How many professions are that interesting I wonder. I am wondering about sports, and how much longer athletes perform in their sport of choice. Not necessarily about mortality but definitely a form of longevity. It seems anyway that for some sports like hockey, more players play at an older age.

Really enjoyed this article and the effort taken to do the analysis. Thank you for the entertainment.

Chris Fievoli: It would be actually be interesting to do a historical study on how the longevity of hockey players has evolved. Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, you had a lot of NHLers (Jacques Plante, Doug Harvey, Terry Sawchuk, Tim Horton) who were playing well past what should have been their expected retirement – unfortunately, in most cases, it was because they needed the money. That obviously has changed, and now players can benefit from superior training and conditioning (and a lot less smoking!). So would we see a U-shaped distribution in career length over the last 50-60 years? Might be something to look at.

Hang Truong: Hi Chis and Joseph, I really enjoyed reading about your research and insights and learned about classic rock performers. Thank you!